The credit belongs to the person who is actually in the arena; whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly; who errs and comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; who does actually strive to do deeds; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotion, spends oneself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement; and who at worst, if he or she fails, at least fails while daring greatly.

-Excerpt from Theodore Roosevelt’s speech, “Citizenship in A Republic” given at the Sorbonne in Paris, April 23, 1910.

When the stakes are high, will students be able to respond with daring? Not if they have had not had the opportunity to deal with failure early and often.

What is a normal reaction to a mistake? It is an emotional one. We are embarrassed. We think we are not smart enough. We may try to hide the mistake. Instead, we should look at a mistake rationally, as an important step in the process towards real achievement.

Likewise, as educators we need to help students see that making a mistake is a typical quality of learning and without errors we can never pinpoint areas of weakness.

What can we do to support risk-taking and mistake making in the classroom?

Create Points of Discomfort

As teachers, we can intentionally put students in places of discomfort in order for them to learn how to fail quickly. This might entail having students work with others on a collaborative project, such as building consensus around a deep issue. This might include putting constraints on time or materials for a building project. You might have students use a technology they have never tried before to present their work to the class. This could be resisting the urge to swoop in and offer hints to a solution or that first sentence to a paper. As a student struggles to answer a question, allow students to squirm and to have to think rather than feed them the answer. The idea is for students to see the struggle as just a normal part of learning.

Practice Failure or Test ‘em Until it Breaks

Second, students need opportunities to actually fail. In a science classroom, this could be creating a design that will be tested to the point of failure. All of the projects will at some point break during testing and when that happens the point is to identify the weakest part of the design and to build a revision that improves on that weakness. In an English class, this could entail a revision process in which every paper is rewritten; students turn a short story into a poem or a non-fiction piece into a short story. In this way, students are playing with form and language. They are revising to practice the revision process, to take a piece of their writing and push its excellence into a new form. This is consistent with Malcolm Gladwell’s notion of deliberate practice in Outliers. A virtuoso violinist does not just practice a piece and skim through the tricky spots, to get to the end. Rather, that violinist will skim through the easy parts and focus on the most difficult sections, practicing them again and again until those parts become fluidly mastered.

Support a Growth Mindset: Work is Fluid

According to Carol Dweck, author of Mindset, there are two mindsets one in which individuals consider intelligence as fixed and one in which learners view intelligence as tied to effort. Students with a fixed mindset see their performance as evidence of their intelligence. Therefore, they are likely to select easy tasks and avoid harder ones and with them any opportunities for failure. In contrast, those who embrace a growth mindset view intelligence as fluid. They see effort as critical to success. They are more likely to embrace challenges because they see the process of acquiring skills as raising their intelligence.

Therefore, to promote a growth mindset, teachers should provide opportunities for students to do retakes on quizzes or turn in multiple drafts of an assignment. You might say to students, “Use a pencil because you are going to change your ideas.” Or “Here is an extra design page because as you build you are going to make revisions.” Dweck’s research shows that even praising student effort rather than intelligence affects their outlook toward learning. Students might read an article like Sowing Failure and Reaping Success: What Failure Can Teach about famous failures turned success and then discuss, reflect, and write about the questions within the article.

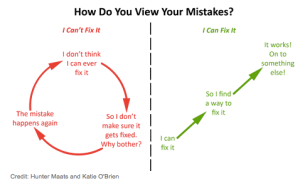

Provide Perspective

Students need to consider not just their mistake but also their reaction to that mistake. By being obsessed with a number a test score, or grades that affect school admissions students will become afraid to fail; they will become averse to take difficult steps to master new material. Instead, we need to help students see the larger picture and their ability to shape it. As teachers we need to encourage a mindset of making an adjustment. Acknowledging that difficulty is a crucial part of learning will reverse a destructive cycle in which stumbling creates feelings of ineptitude that in turn halts learning.

Here is a helpful diagram from Teaching Students to Embrace Mistakes:

And finally on a personal note– When I was in high school, my father taught me how to play squash and on that afternoon gave me a 6-point handicap for an 11-point game. As he beat me for a second game, he barked at me, “Make a friggin’ adjustment!” Though I was tired and frustrated, I thought about what he said as we started the 3rd game; rather than make the safe shot I started going for the angle, tried to dominate the center of the court, and got a little more physical. The momentum changed and I beat him. “There you are” he said to me as I paraded jubilantly around the windowed court. He was right. If you continue to play the same way, the outcome will be the same. It was only in taking a risk, making a change that I experienced success. Though we will all make mistakes, the important part is learning from those mistakes.

And to end, I quote Danish physicist Niels Bohr who once said, “An expert is a man who has made all the mistakes which can be made, in a narrow field.”

Risk taking and failing are one of the best ways to assess a learners current proficiency level, particularly when learning a second language. Success and failure at risk taking are what formative assessment is all about. The outcome shapes how we move forward.

http://wlteacher.wordpress.com/2014/10/25/the-proficiency-based-foreign-language-classroom/

http://wlteacher.wordpress.com/2011/03/12/summative-and-formative-assessment/

Joshua

World Language Classroom Resources

http://wlteacher.wordpress.com/